Nature

Dry Summer Photos – June 2024

Our little corner of the world has an interesting summer season. We often talk about having a 5th season . See https://youtu.be/UQ2g_0wjIUE where we describe a Hot Dry Summer and a Monsoon Summer.

We have now entered the Hot Dry Summer. In Madera Canyon, we see it in multiple ways. Madera Creek dries up, the spring flowers have disappeared, and the grass lands become quite dry and are a real fire hazard. Animals avoid the hot sun. A walk through Madera Canyon is generally a quiet experience, especially if you walk later in the morning or in the early afternoon. Many people don’t visit the Canyon in the hot dry summer. I often hear – “there is nothing to see”.

To counter that, I took a late morning walk this last weekend on the Proctor Trail, with the temperatures well over 90 degrees. I took a number of photos, coming easily to the conclusion that if you pay attention, look around, and look in the shade, you will see quite a lot. Take a look at the photos now in the Photo of the Month for June.

See them on our Flickr page https://www.flickr.com/photos/198518361@N07/albums/72177720317757295 .

So come and visit Madera Canyon before the Monsoons start. And once the Monsoons begin, visit again and see the multiple changes that occur in a short time.

2024 Spring Wildflowers

Doug Moore

Last month, with the first hints of spring coming to southeastern Arizona, I made some hopeful predictions for a good spring wildflower bloom in the canyon. After timely late fall and winter precipitation, all indications were good. Now in late March- following warming daytime temps and even more rain- I’m happy to report that many flowers are indeed blooming!

As of March 26, the lower canyon above Proctor is becoming verdant. The cottonwoods along the creek are fully leafed-out, while mesquites & sycamores are just now popping new leaves. The lush green carpet of “fuzz” spreading profusely over the ground as perennials & annuals sprouted, has matured into the blooming rosettes of Mexican Gold Poppy, Blue Phacelia, Desert Anemone, Nevada Biscuit Root, Desert Hyacinth, Golden Smoke, and a variety of wild mustards. Silver Puff- our tiny-flowered version of yellow dandelions- is also common this year. The brilliant poppy show around the Proctor Ramada is especially pretty.

Native understory shrubs will be producing a show soon also. Arizona Desert Thorn, a wolfberry, is full of tiny pink bell flowers and globemallow shrubs are budded up with the few first orange blossoms showing. Fairy Duster around the parking area is leafing out; their pink pompom flower clusters will follow close behind. Desert Honeysuckle is in leaf all along the trail in the mesquite bosque & on the left trail above the split. A banner season for their orange trumpet flowers appears imminent- happy days for hummingbirds and insect pollinators!

As noted last month, as we move on through spring, different trees, shrubs, perennials and annuals will flower. The bloom will gradually move up into higher elevations in the canyon. I’m scanning the trail between Proctor and White House for stalks of deep-pink Perry’s Penstemon and magenta Ribbon Four O’clock. I’ll also be watching for scarlet Claret Cup Hedgehog cactus flowers on the cliffside above the White House Bridge, and waiting for the scarlet trumpets of Smooth Bouvardia shrubs to bloom below the Claret Cups along the burbling creek.

Happy spring and good wildflower hunting!

LICHENS

By Penny France

Freddy fungus and Alice algae

took a lichen to each other, but

their marriage was on the rocks.

You have probably seen the green, crusty lichens living on the surface of rocks in Madera Canyon and walked right on by. These initially-unappealing lichens are more interesting than you could ever imagine. Since this year seems to be is an especially good year for seeing healthy specimens, now is a perfect time to learn more about them.

It is estimated that about 8% of the earth’s surface is covered by lichens and that there are at least 3,600 varieties of lichen just in North America. Lichens constitute the sole vegetation of extreme environments such as the Arctic tundra. They can live in hot dry deserts, and in coastal habitats where fog and water vapor abound. Lichens are successful in colonizing on rocks, on or inside the bark of woody plants, on wood, soil, mosses, leaves of vascular plants (especially in the tropics), and even on other lichens, as well as on man-made substrates such as concrete, glass, metals and plastics and slag heaps. Further, they are considered to be among the oldest living organism. An arctic species, has been dated as being about 8600 years old

Just what is a lichen? Notice that we haven’t called it a plant; it’s not a plant. The lichen does not have vascular tissue like a plant’s xylem and phloem to move nutrients and water around nor does it have the waxy cuticle like leaves on plants have. The unique characteristic of a lichen is that its life depends on a combination of two organisms—the fungus and the alga. The more numerous fungi cannot produce food but can provide moisture, fight off disease and provide growth functions. Fungi are known for their role in decomposition of organic matter. The alga partner photosynthesizes and provides food for the fungus so it can grow and spread. They rely on each other to provide life. It’s called a symbiotic relationship. There are over13,500 kinds of fungi species in the world. The name of the fungal species prevalent in a lichen serves as the name given that lichen.

Read More

The lichen’s general structure is composed of layers of fungus threads and green and/or blue-green cyanobacteria alga that together form the interior of the thallus. The thallus is so integrated into the fungus/alga mix that only recently has it it been studied as a single organism in the lichen. The thallus lies against the substrate and has no clearly-defined stems or leaves.

Lichens grow slowly, live a long time, are stress tolerant, and come in many colors and shapes (some even resemble minute forests). The outer layer inside the thallus is the cortex and provides a little protection and color, in some species. The algal layer usually tells us, by color, the kind of alga a lichen has. When dry, it is usually gray or matches the cortex color but, when wet, those cells become transparent and the algal cells underneath show their color. Cyanobacteria can be a layer under the upper cortex or in small pockets on top of the cortex. If there is a green algal layer already present, it will give the lichen a dark green, brown, or black color. In some lichens however, there are no layers of fungus and alga. The individual components are mixed together in one big uniform layer and the resulting growth form is gelatinous. These types are called jelly lichens—definitely qualifying as a unique shape.

How do lichens attach themselves to a substrate? There are a couple of ways. Rhizomes are fungal filaments that extend out and hold the lichen down to whatever it is sitting on—the substrate. The other way is the “holdfast,” an extension of the lichen thallus. Some lichens have a central peg or holdfast that attaches to the substrate—typically a rock—kind of like an umbilical cord.

About one billion people globally eat lichens as part of their diet. They are used to prepare indigenous foods, beverages, spices and animal feed in various cultures around the world.

Since the fungus can protect its algae, the normally water-requiring lichens can live in dry, sunny climates without dying as long as there are occasional rain showers or flooding to let them recharge and store food for the next drought period. Further, lichens provide a means to convert carbon dioxide in the atmosphere through photosynthesis into oxygen, which we all need to survive.

In recent years, lichens have become more frequent subjects for scientific research. Their unique symbiotic association between alga/cyanobacterium and a fungus produce secondary metabolites that offer promising drug leads. To quote an article in an August 2022 Journal of Ethnopharmacology entitled “Lichens: An Update on their Ethnopharmacological Uses and Potential as Sources of Drug Leads”: “Natural products are low molecular weight molecules produced by living organisms (plants, animals, and microbes) and have been traditional leads for medicines for ages. They have a historic significance as important novel compounds which are useful as drugs, models for synthetic/semisynthetic structure modifications and optimization, biochemical and pharmacological probes…”. “Natural product molecules and/or their synthetic modifications, have been particularly useful for chemotherapy of cancer and malaria.” “…introduction of new therapeutic agents has not kept pace with the increase in the evolution of multi-drug resistant microbial strains, making many infections untreatable. There is therefore a dire need for novel drugs.”

So that ho-hum lichen we routinely walk by without noticing has something pretty special about it that is well-worth our attention and appreciation.

Photos by Jim Burkstrand

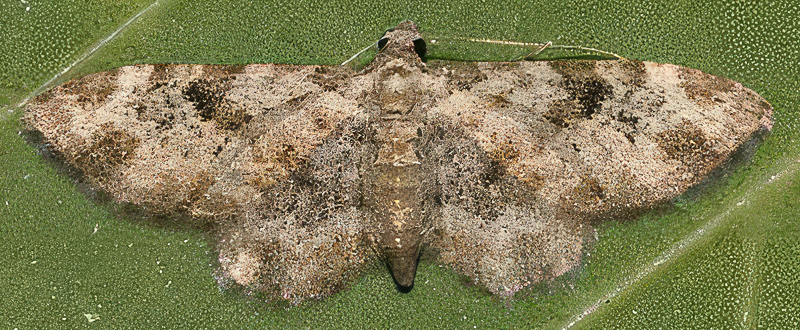

A New Moth with a Type Locality in Madera Canyon

A new geometrid moth Eupithecia neremorata (Ferris & Russo, 2023), with a type locality in Madera Canyon.

Photography by Charles Melton

By John Murphy

More than 100 species have been described with type specimens from Madera Canyon. The most recent is the geometrid moth Prorella neremorata described by Ferris and Russo in late 2023. By the time the new description was published the higher level classification had been revised and its name changed to Eupithecia neremorata (Ferris & Russo, 2023) by Schmidt & McGuinness (in Pohl & Nanz (eds.) 2023). Eupithecia neremorata is a member of the remorata group.

References

- Ferris, C.D. & J. Russo, 2023. Review of the Prorella remorata Group with Description of a New Species from Arizona (Geometridae: Larentiinae: Eupitheciini). Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society, 77(4): 226-234.

- Pohl, G. R. and S. R. Nanz (eds.). 2023. Annotated Taxonomic Checklist of the Lepidoptera of North America, North of Mexico. Wedge Entomological Research Foundation, Bakersfield, California, xiv + 580 pp.

Trogonids in Arizona, How far do I have to walk?

Other Reading on Nature:

News from the US Forest Service (USFS)

The USFS wants to share that the USFS Madera Canyon Recreation Guide is now available online in English and Spanish.

You can navigate to them (and the other guides that have been developed) on the website by selecting Visit Us > Maps & Publications and then scrolling down to "Recreation Guides."

The USFS also created a new landing page for Madera Canyon on the Forest's website. You can find it here.

The USFS also created a new landing page for Madera Canyon on the Forest's website. You can find it here.

You can navigate to it on the website by selecting Visit Us > Destinations > Madera Canyon