Cultural History of Madera Canyon

Native Peoples lived in and around the Santa Rita Mountains for thousands of years. Artifacts of early O’odham tribes, including grinding holes or morteros can be seen in Madera Canyon. Father Kino’s missionary travels in the late 1600s passed by the Canyon, bringing cattle to the area, which became the genesis of large Mexican cattle ranches.

After the Mexican-American war of 1848 and the gold rush of 1849, large changes began. The land was ceded to the United States with the Gadsden Purchase and the great Western migration began. Madera is the Spanish word for lumber and, as ranchers and miners swarmed west, the first commercial undertaking in Madera Canyon was a lumber camp. A road was built from the Canyon to the main Tucson/Tubac road to haul the lumber.

The Civil War, however, quickly reversed the migration. As the U S soldiers left to fight in the East, Apaches descended on the new Territory, causing a majority of settlers to flee. Many stories are told of Cochise, Geronimo, and their braves in the Canyon. Soon after the soldiers returned from the war, the Apache was repressed and the population again grew. Ranching and prospecting in the Madera Canyon area resumed.

The oldest known permanent structure in Madera Canyon is believed to have been built by a sheepherder around 1880. A few years later, it was used by a Tucson Merchant as a summer retreat. He is thought to have whitewashed the adobe structure and the Canyon became known as Whitehouse Canyon. The house later was the home of the Morales family for about 30 years. Remains of the building can still be seen.

In early 1900 prospecting was rampant in the Santa Ritas. Over a dozen mines were operating in Madera Canyon. One was operated by a colorful character who had been a gun for hire and served as a Marshal in Dodge City, Tombstone, and other Western towns. He built a home in Madera Canyon and was later elected sheriff of Pima County. His wife became the County Superintendant of Schools.

In 1905 Madera Canyon and the Santa Rita Mountains became a part of the new National Forest System. In 1911 another Tucson businessman formed a group of backers who built a number of cabins in the Canyon on land leased from the Forest Service. Over the next few years, the roads were improved, automobiles came into use and Madera Canyon became a popular summer destination. In 1922, the Santa Rita Trails Resort was built. The original lodge burned, but in 1929 it was rebuilt as a year-round resort with cottages, cabins, restaurant, general store, gas station and post office. In the 1930s, Madera Canyon was home to a Civilian Conservation Corps camp. Many of the rock walls they built still exist.

The Forest Service continued to develop utilities and improve roads, but eventually the impact of people in the Canyon led to erosion, sewage, and water supply problems. It was decided that the houses on leased land must be removed. Over 50 cabins were torn down between 1984 and 1991. The few homes left in Madera Canyon are on private land. Madera Canyon continues to hosts visitors from nearby communities and from around the world who come to hike, bike, walk, picnic, camp, view the amazing variety of plants and wildlife, or just to experience the joy of nature.

Learn more about the canyon history in “A History Of Madera Canyon,” published by FoMC and available on Amazon and in Madera Canyon at the Santa Rita Lodge Gift Shop.

White House, Madera Canyon, late 1880. Photo: The Arizona Historical Society.

Archaeological Survey of Grasslands, by Cynthia Benedict

Cynthia Benedict documented 46 prehistoric archaeological sites affiliated with the Hohokam, ancestors of the O’odam-Piman people, who inhabited the Sonoran desert from AD 650 until 1450 when the communities began to reorganize and relocate. Her archaeological survey of the Santa Rita Experimental Range east of Green Valley covered 53,159 acres (~ 83 square miles). The sites included artifact scatters, agricultural sites for agave cultivation and roasting, plant (food) processing sites, small campsites, village sites with trash mounds, and one rock-art site.

Read more . . .

Still the largest archaeological survey effort in the area, the survey demonstrates that the bajada supported valuable natural resources and attracted prehistoric peoples who utilized the area extensively for resource procurement, agriculture, and habitation.

Archaeological sites are common on upper bajada settings throughout the Tucson Basin, an area conducive to human settlement for millennia because soils are suitable for agriculture, valuable stone resources in the mountains, and abundant plant resources. All of these resources were valued and utilized by the Hohokam that inhabited villages on the upper bajada as well as the lower bajada nearer the Santa Cruz River. The entire area around Green Valley, extending to the base of the Santa Rita mountains, is rich in archaeological resources.

Archaeological Survey of Grasslands, by Cynthia Benedict

These surveys are necessary in order to identify sites, assess the potential impacts of proposed development, and plans to mitigate impacts. Mitigation is often done through project redesign or data recovery (excavation).

Archaeological resources are fragile and irreplaceable. Given the population expansion in the Tucson Basin, there are few areas left where archaeological sites have remained largely protected from development. The desert grasslands of the Santa Rita Experimental Range including the private lands at the base of Madera Canyon is one of those places. These resources have the potential to yield valuable information, add to understanding of prehistoric settlement of the area, and enhance the character and intrinsic value of the land by the presence of its archaeological resources. Photo: Stone tools, arrowheads, dart points, bifaces found.

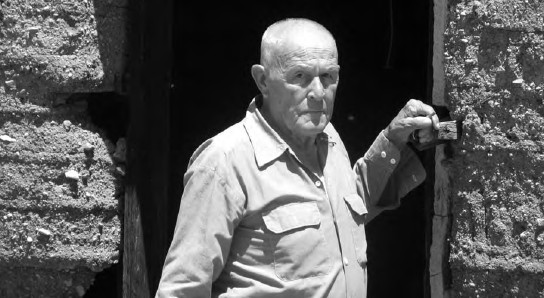

A Survivor's Story By Frances K. Russell

In the 19th century, Arizona ranching families had to be tough, and the Proctors were.

Printed with permission of Robert Proctor and Range Magazine, Winter 2010.

George Proctor says “We were reared on the Proctor Ranch in the Madera Canyon/Box Canyon area south of Tucson at the edge of the Santa Rita Mountains. Ranching was rough. As I look back, it is hard for me to imagine how we survived.”